And even though such interruptions are quickly addressed, with local authorities vowing to step in with emergency funding, such instances are widely regarded as a sign of weakening local fiscal capabilities.

The government’s economic capability to enforce social and administrative governance has been greatly weakened

Other signs include lower wages, or even missed salary payments, among public servants and public institution workers; a sharp rise in local borrowing; and large fines for corporations.

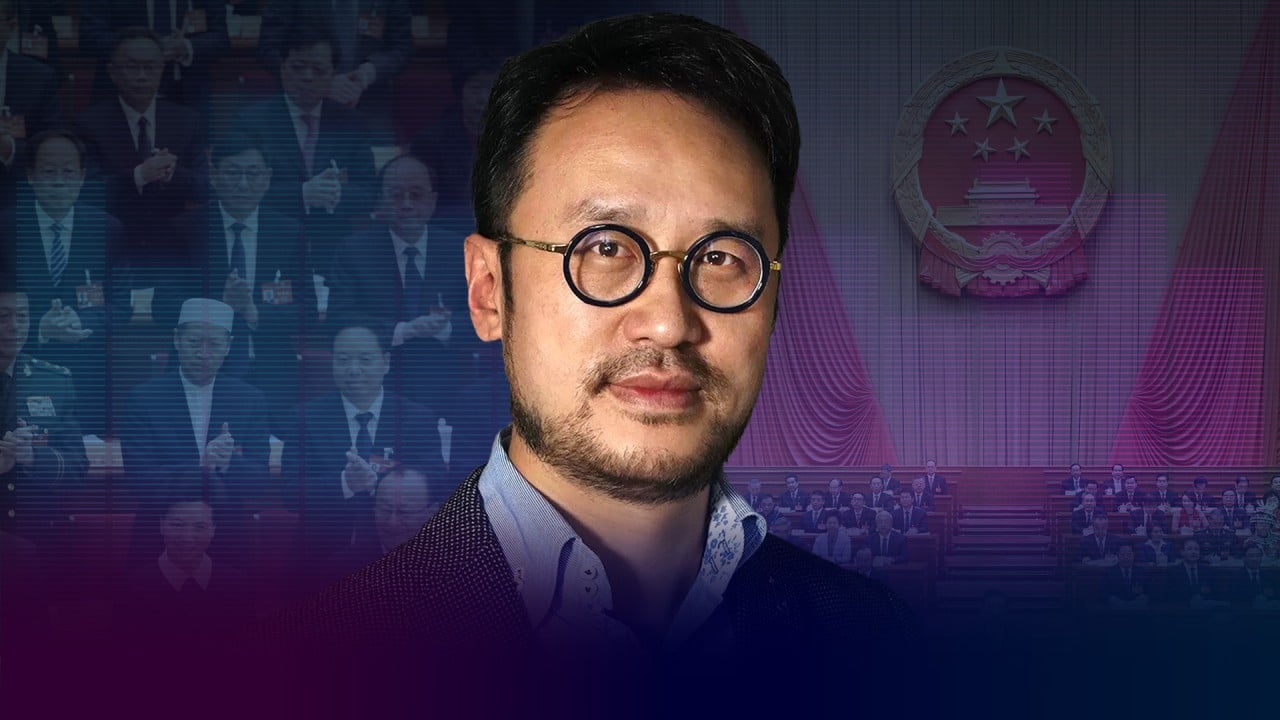

“The government’s economic capability to enforce social and administrative governance has been greatly weakened,” said Zhou Tianyong, a professor with the Dongbei University of Finance and Economics and a former senior researcher with the Central Party School in Beijing.

“The decline in taxes and fees, either in relative or absolute terms, is the result of an economic slowdown, straining public revenues and expenditures and subsequently resulting in a weakening of economic governance capability,” he wrote on his social media account on Monday.

There are some glaring causes for these local-level fiscal dilemmas, including the pandemic-induced slowdown, as well as falling property taxes and land sales.

However, economists also point to China’s 30-year-old fiscal and taxation system, saying it allocates most of the fiscal revenue to central government coffers, and has led to a massive amount of unregulated borrowing and frenzied land sales at local levels to fund their operations and grow their economies.

“The fiscal and taxation reform 30 years ago has not been thoroughly implemented. Problems have built up to make the situation more complex, and they have reached a point that changes must be made,” said Tang Dajie, a senior researcher with the China Enterprise Institute, a Beijing-based private think tank.

“A core task is the need to redefine the [economic] relationship between the central and local governments, and to boost the local taxation system.”

Beijing had launched reforms three decades ago to recentralise fiscal revenues, and in the first year of its implementation in 1994, the central government’s fiscal revenue nearly tripled to 290.7 billion yuan, while local revenue fell by nearly a third to 231.2 billion yuan, according to the National Bureau of Statistics.

Today, a vast majority of provinces or cities have to shoulder a wide range of expenditures – including payroll for public servants, public transport operations, the construction of hospitals and schools and basic urban developments.

The local debt piles and deteriorating credit profiles have grown so problematic that some regions have reached out to Beijing for help.

A major problem is that, in the past three decades, no real tax-sharing was institutionalised below the province level

And since Beijing announced in late April that the gathering would take place in July, expectations have been running high for leadership to offer some impactful remedies to what ails the nation’s economy.

Jia Kang, former head of the Ministry of Finance’s research institute, said that the 1994 fiscal and taxation system contributed greatly to establishing a framework of “division of economic power”, but such tax-sharing happens only between central and provincial governments.

“A major problem is that, in the past three decades, no real tax-sharing was institutionalised below the province level,” said an excerpt from one of his speeches, posted to his WeChat account in late May.

“This is a very important reason behind the current mess – the difficulties of grass-root operations, hidden liabilities, and short-sighted behaviour such as the reliance on land-sale revenue.”

While tax revenues and land incomes have fallen, many municipal- and county-level governments are increasingly relying on the central government.

Transfer payments from Beijing reached a record high of 10.3 trillion yuan last year, which was only slightly less than the local fiscal revenue of 11.7 trillion yuan.

Meanwhile, non-tax income – including administrative fees, government funds, land income, fines, and confiscated assets – has continued to rise. In 2023, 16.4 per cent of China’s fiscal revenue came from non-tax items, the Ministry of Finance figures showed.

“The vertical structural imbalance between the central and local governments within the fiscal system is the root cause of constraints on the healthy and sustainable development of the fiscal system,” a government-linked think tank, the National Institution for Finance and Development (NIFD), said in a report last month.

China has yet to develop a legal framework to specify the powers of tax legislation between the state and local governments.

The new round of fiscal and taxation system reform should further reform the revenue and expenditure structure of central and local governments

The central government takes care of expenses related to defence and diplomacy, but local governments have a growing responsibility in spending related to science and technology, as well as financial regulatory matters.

Localities also shoulder costs associated with education; culture and media; social security and employment; medical and healthcare; infrastructure; and environmental protection.

In 2023, 99.8 per cent of spending in urban and rural community affairs came from local government coffers, the NIFD said.

“Therefore, the new round of fiscal and taxation system reform should further reform the revenue and expenditure structure of central and local governments, especially the powers and expenditure responsibilities,” it suggested.

In an article published last year, former finance minister Lou Jiwei, who helped design the 1994 fiscal and tax system, listed three key tasks to tackle, including the establishment of a local tax system, resolving implicit local debt and setting up a system aligning administrative power with expenditure responsibilities.

It is a complex, systematic project

“Property tax is the most suitable type for the local tax system,” he said, adding that pilot programmes “should be expanded as soon as the economy recovers”.

Lou also suggested revamping the consumption tax, by turning it into a source of revenue shared by central and local governments, however, he acknowledged the difficulty of administrative power reform.

“It involves relations between the government and the market, the government and society, as well as central and local governments, and it covers a wide field such as politics, economy, society, culture and ecological civilisation,” Lou said.

“It is a complex, systematic project.”

Xu Shanda, former deputy director of the State Administration of Taxation, has advocated for the central government to take over the costs of social security, though he said the state should be responsible for only minimum pension provisions.

“The obstacles to tax reform are similar to the obstacles to rebalancing the economy away from investment and toward consumption,” said Logan Wright, director of China markets research at the US-based Rhodium Group.

“The intent to shift the tax system will coincide with a more concerted effort to rebalance the economy – but it is not evident at present.”

In its 2021-25 development plan, Beijing outlined intentions to “gradually” raise the proportion of the so-called direct tax in its overall revenue, to improve the local tax system, to cultivate local tax sources, and to enhance the personal income tax structure.

But local fiscal conditions have been deteriorating at an accelerated pace.

And while Beijing could opt to ramp up support and offer greater lifelines at the third plenum, some analysts are curbing their expectations.

“The new round of tax reform is not a major overhaul of the current tax system, but is based on the established main framework of the modern tax system,” Yue Shumin, a finance professor at Renmin University, said during a webinar in April.

“[The goal] is to ensure smooth operations and enhanced functionality, and to steadily advance the maturity and standardisation of the modern tax system.”

Other pundits are expecting low-hanging fruit, such as an expansion of the scope of personal income tax to address income inequality, or the simplification of the rates of value-added tax (VAT) – the top source of income for the Chinese government.

VAT revenue saw a year-on-year drop of 7.6 per cent to 2.58 trillion yuan (US$355 billion) in the first four months of 2024, according to government data.

China employs a three-tier system for VAT rates, and has said it would simplify to two-tiers, although the changes may reduce VAT revenue. However, such changes have yet to materialise.

I don’t think that the third plenum will be able to completely solve the problems that have emerged during China’s economic and social transition in one step

VAT forms a substantial part of China’s revenue, accounting more than a third of China’s overall tax revenue, and is shared between the state and local governments.

Streamlining the collection of VAT could also help companies receive refunds quicker, and Chinese lawmakers are in the process of drafting a VAT law, with a third reading expected at the end of 2024.

Some options that have been put forward by scholars that could boost China’s tax base is a digital services tax, which could capture the rapid growth of the e-commerce industry, as well as expanding the scope for environment protection taxes to cover more areas to help reduce waste and carbon emissions.

“I don’t think that the third plenum will be able to completely solve the problems that have emerged during China’s economic and social transition in one step, but it will certainly break new ground,” said Jia, the former finance ministry researcher.

Jia added that China needs “round after round of reform” that would be difficult, but urged “patience and courage” to seize opportunities.

Post a Comment